We owners know intellectually that our dogs’ lives pass by much more quickly than our own, but when they begin to fail, it’s utter torture.

We owners know intellectually that our dogs’ lives pass by much more quickly than our own, but when they begin to fail, it’s utter torture.

Lobo wasn’t a big fetcher, but over the years, Jon had convinced him to go out to get the morning paper and carry it back to the house for a treat. This was always subject to Lobo’s mood that morning, and his periodic refusals were evidence that he could hold himself above bribery. Sometimes he’d go at it with real enthusiasm, throwing the paper up in the air or ripping it to shreds. Other times he’d decide to take it over to his outdoor bed, as if he was planning to lounge there with his coffee. But eventually, he just didn’t want to spend his waning energy on this ridiculous routine. He’d bark at Jon to remind him to go, but then he’d sit on the step and just wait.

Horseback rides with Jon were once a non-negotiable. It was evidently a manly thing to do to go out with the neighbor men, even when it meant trotting for miles, lying down in the shade and panting when necessary, and begging water from Jon. Even in later years when he’d be sore for days, he was not about to be left behind. When his arthritis became obvious, Jon left him once with me. He kept scanning for the horses in the distance and howling and crying. He knew he couldn’t do it any more, but it was as bad for him as it is for some elderly people to have their car keys taken away.

For years when we took him to our place in the mountains, Lobo would be delighted to take advantage of “ranch rules,” which allowed him to get up on the furniture. But eventually, leaping up on our bed was impossible, and he was relegated to the rug.

When he started refusing to take walks, we knew something was really happening inside that big dog body. He would lie on his outdoor bed and just stare at me with his ears down, a clear “No, thanks.” He would go with Jon up until the very end, when we had to agree with the animal communicator that he was getting ready to leave his body.

Lobo’s last lesson was how to die well. He did what he wanted, following his own instincts rather than our wishes. He was extra affectionate, approaching us almost every day just to stare into our eyes. He talked more, developing sounds that became an understandable language. And when it became clear that there were no options left except his suffering, he had loved ones around him singing and drumming and feeding him all the treats he wanted. I would love such a farewell.

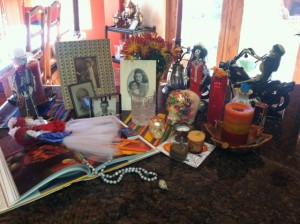

We sprinkled Lobo’s ashes in his favorite places around the house. Some under the mesquite trees where he buried bones, treats and the horse brushes he had stolen. The container of ashes had sat for weeks on a little kitchen shrine with a Day of the Dead dog figure with a paper in his mouth. Next to it was a card from the vet that always made us laugh. It was to Jon and Patty. (Patty was Jon’s first wife back in the 70’s. Someone’s records need updating.)

As I write this, Jon is away on a fishing trip, and the house is absolutely silent. No need to go out and remind Lobo not to bark. The house hasn’t been cleaned for two weeks, because there’s no dog hair. If Lobo were here, he’d be depressed and would be doing a lot of waiting up on his outdoor bed. And so I tell myself there are advantages. The squirrels and birds are happy he’s gone. But I haven’t been able to get rid of his outdoor bed. Sometimes when I drive in, I think I see him there, scanning the yard, making sure the area is safe for me.

Surely we’ll get another dog. And surely we will love that one, and cry again when that one dies. But I know we’ll never forget Lobo. Just like any member of the family, there are no substitutes.

He was indeed, my teacher.